|

Works and Concepts

|

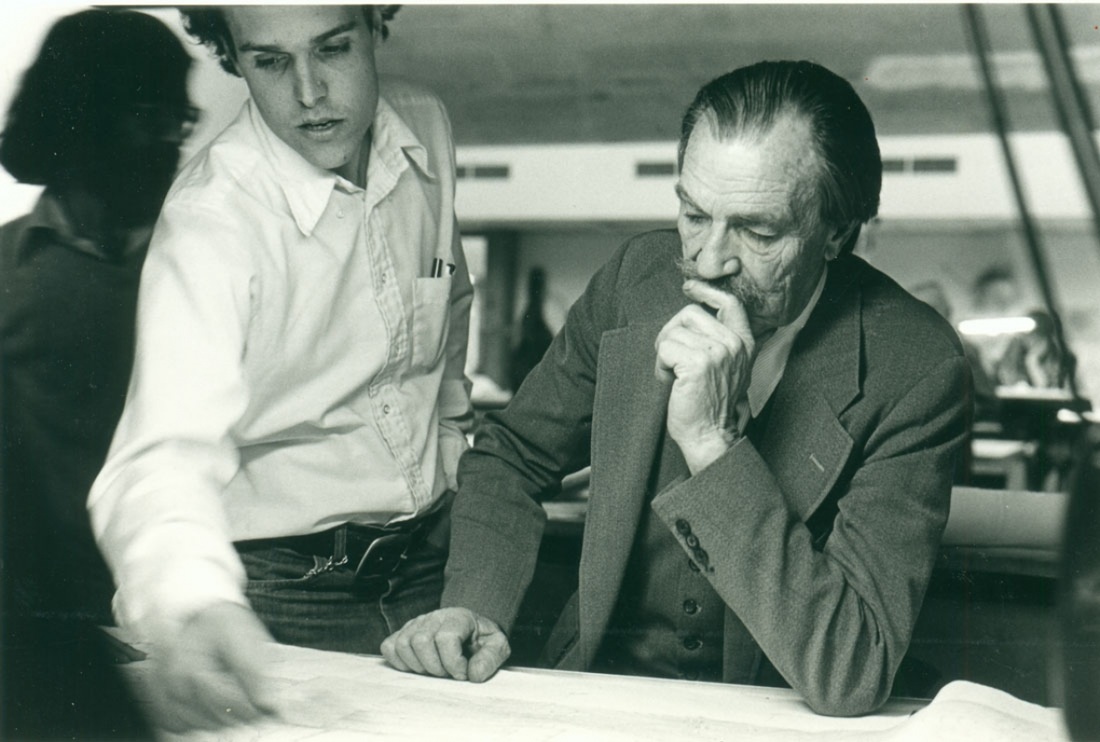

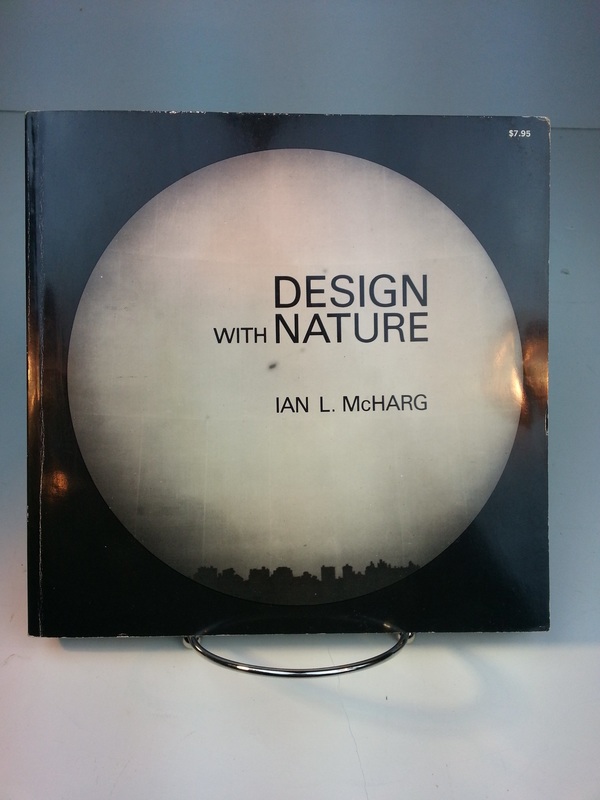

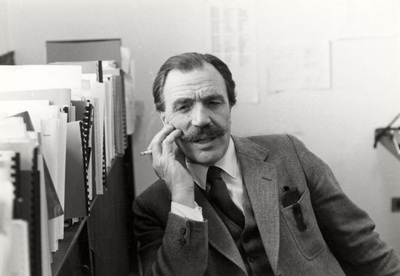

In Fall 1957, McHarg offered a class; Man and Environment was a class that grew vastly in popularity [1]. McHarg later modeled his TV series “The House We Live In” on the class, interviewing the great minds of the time irrespective of discipline for both, on matters involving environment, man’s involvement, and anything relating the two [1] [4] [6]. He believed that any struggle was one which could only be understood, unraveled, and a solution sought, by using a combination of the sciences and disciplines involved [5]. The class and TV series were the coalescence of ideals, thoughts, and observations which arguable became McHarg’s magnum opus, if not in theory then in its impact on the world well beyond the boundaries of landscape architecture. Design with Nature was the book which made many sit up and take notice. Niall Kirkwood, a practicing architect at the time, had a life changing experience reading McHarg’s book. Revkin quotes Kirkwood saying "I sold everything and left London to study under Ian" [7]. He was far from the only one.

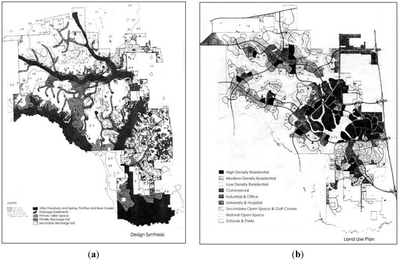

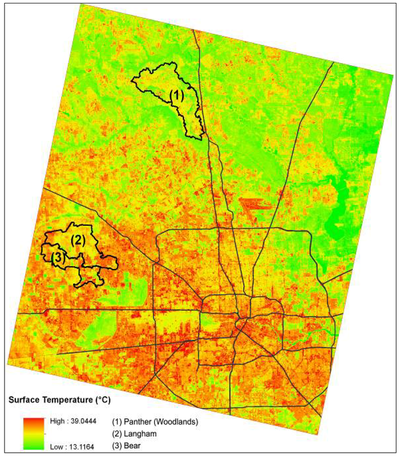

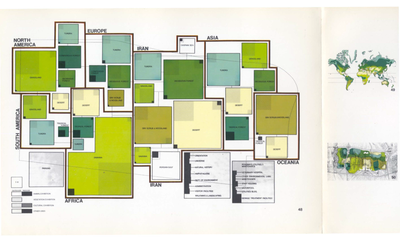

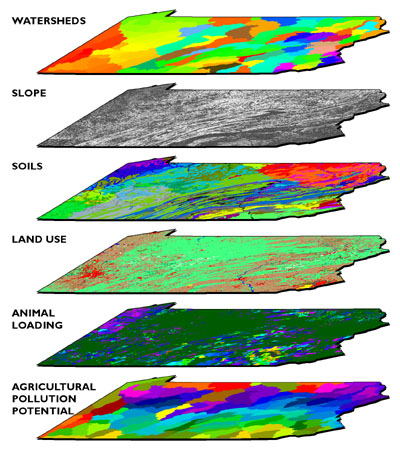

As the classes and public involvement grew, so too did his research. McHarg used the classes as a springboard to launch his research from, pulling his students along with him. In his speech "The Garden as a Metaphysical Symbol" he drew harsh comparisons to monotheistic religions and the assumption of (God-given) rights to dominate the earth. He used Eden as a point of conflict for humanity; the snake and the tree were of nature which incited man's fall from grace, Genesis was painting nature as evil and not to be trusted but overcome [3]. That is how he felt humanity saw the earth, and what he fought his entire career, if not longer, to overcome. McHarg believed that the separation of religion, science, and art were a mistake, and that was what precipitated the aimless, valueless direction of humanity [3]. Part of the reintegration of these pieces of life was led by example; McHarg developed theory, and put it to practice, using science and data from a wide spectrum of disciplines in order to create his design concepts, using what came to be called "layer cake" maps [7] (Figures 4 & 5). In this he emphasized the process for what would later become the GIS system: a multi-disciplinary, gathering process utilizing various data maps to gain a cohesive picture, which we now use in many disciplines. We even have drawn the concept into gaming, a world can be created at levels with landscapes which touch on different sets of geographical knowledge and behave as such. McHarg enthusiastically believed that computers would allow for quicker and more definite resolutions to questions regarding maps, and has been criticized for his absolute belief in the answers layer cake maps and science gave [2]. |

Works and Philosophy

|

I would argue that McHarg’s most vital works were ultimately not truly physical manifestations such as projects. He worked on them, and the concepts evolved over time, in some cases beyond his lifetime. While McHarg did have physical projects both completed and interrupted, his works were more manifestation of his conceptual theories. I would even venture the opinion that they were trials and experiments, especially since we are still using them as proof-of-concept today [9].

The first major contribution is often overlooked despite being critically valid to many disciplines. The concept of looking at ecology as a “layer cake” of reports and environmental data fields superimposed one over the other, to create an overarching pictographic or conceptual image of the land as a whole is priceless. Mylar transparency maps of a single location stacked [7] over a base map [2] to flesh out the meaning gave unprecedented opportunity for collaboration, and a visual interpretation for that information as a cohesive whole. A geologist could give graphic representation of landmass and rock deposits of an area which were palatable to a landscape architect, or wildlife scientist who could then use that information to design for their constituents around (or better yet in concert with) those land forms. Hydrology reports, population density, and traffic usage and patterns are other examples. That concept grew into what designers, environmentalists, ecologists, geologists, hydrologists, and many more use in today’s variations of the Geographic Information System(GIS) system. The publication of Design with Nature is possibly the most well-known, and it represents a series of ideas which were the compilation of his classical thoughts regarding the ecology of the environment, and man’s relation to it. While this book enabled McHarg to broaden the scope of his audience vastly, it ultimately is not the pinnacle of his thought or impact. McHarg’s most vital and lasting impact is his teaching. For about thirty years McHarg influenced students’ minds as well as formidable academic minds of the time with his emphatic views and interviews, and that passion was distinctively passed on to generations of pupils [7] [8]. He was a gifted wordsmith; decisive in his spoken and written words. The convictions behind those words in combination with a world ready to receive his concepts lead to a revolutionary reaction, and rapid shift in design thinking. |

“Of all the things you can say about planning, one thing is certain: it can no longer be done by one person. And if you can determine what the planning problem is, then that determines the disciplines that must be involved in the solution to the problem.” |

Critique and Reflections

As a short chronological timestamp: in 1909 the first National Conference on City Planning was guided in part by the Olmstead generations of landscape architects. In 1962 Rachel Carson published her book Silent Spring [8] (although at the time of its publication it was ignored by the general populace), and in April 1970 America initiated Earth Day. Although McHarg was involved in the last item, these highlight the views of the scientific, academic, and social communities as they slowly shifted.

McHarg took credit for much with implementation prior to himself. According to Susan Herrington, the concept of layering data was used in several other instances prior to McHarg [2]. He also claimed initiation of ecological city planning [3]. Anne Spirn, a student who later worked with McHarg, comments that he, like others, strove to “invent the wheel” on his own, losing the opportunity to perfect others’ work at the cost of final concepts which struggled at the same issues and therefore failed to advance past the rest in many ways [2]. He was very aggressive in his views and despite his attack on monotheism as self-important and empowering [3], he was just as self-determinant, and hardheaded in his approach to flexibility on his views. However this decisiveness is what gave him such power, and the surety that he would create change was what gave him the edge needed to change minds and alter general opinions. He was needed for the revolution of thought which became a sense of environmentalism as a whole, and I would argue that for all of his faults his involvement was indispensable and critical to ecological design.

McHarg took credit for much with implementation prior to himself. According to Susan Herrington, the concept of layering data was used in several other instances prior to McHarg [2]. He also claimed initiation of ecological city planning [3]. Anne Spirn, a student who later worked with McHarg, comments that he, like others, strove to “invent the wheel” on his own, losing the opportunity to perfect others’ work at the cost of final concepts which struggled at the same issues and therefore failed to advance past the rest in many ways [2]. He was very aggressive in his views and despite his attack on monotheism as self-important and empowering [3], he was just as self-determinant, and hardheaded in his approach to flexibility on his views. However this decisiveness is what gave him such power, and the surety that he would create change was what gave him the edge needed to change minds and alter general opinions. He was needed for the revolution of thought which became a sense of environmentalism as a whole, and I would argue that for all of his faults his involvement was indispensable and critical to ecological design.

Image and Figure Gallery

References

- Corner, James. "May/June Gazette: Obits: Ian McHarg." May/June Gazette: Obits: Ian McHarg. 2001. Accessed December 1, 2015. http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0501/mcharg.html.

- Herrington, Susan. "The Nature of Ian McHarg's Science." Landscape Journal 29, no. 1 (March 2010): 2-20. Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed December 1, 2015).

- McHarg, Ian L.. “THE GARDEN AS A METAPHYSICAL SYMBOL”. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 128 (5283). Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (1980): 132–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41373057.

- McHarg, Ian L.. The Essential Ian McHarg Writings on Design and Nature. Edited by Frederick R. Steiner. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2006.

- McHarg, Ian L.. Ian McHarg on City Planning. Berkeley Planning Journal, 3(2), (1988). ucb_crp_bpj_13178. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gj2n3d1.

- Pioneer Ian McHarg. "Ian McHarg." The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Accessed November 30, 2015. https://tclf.org/pioneer/ian-mcharg.

- Revkin, Andrew C. "Ian McHarg, Architect Who Valued a Site's Natural Features, Dies at 80." New York Times - Arts. March 12, 2001. Accessed November 30, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/12/arts/12MCHA.html.

- Spirn, Anne Whiston. "Ian McHarg, Landscape Architecture, and Environmentalism: Ideas and Methods in Context." In Environmentalism in Landscape Architecture, edited by Michel Conan. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2000.

- Yang, Bo, Ming-Han Li, and Shujuan Li. "Design-with-nature for multifunctional landscapes: environmental benefits and social barriers in community development." International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health 10, no. 11 (October 28, 2013): 5433-5458. MEDLINE with Full Text, EBSCOhost (accessed November 29, 2015). www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/10/11/5433/pdf.